“When “Conservation” Becomes Colonisation” - 31 October 2025

How Pāua Restoration Exposes the Neoliberal Gutting of Our Moana

Kia ora koutou,

While five Hauraki Gulf iwi scramble to save functionally extinct pāua populations with volunteer labour and crowdfunding, the same corporate fishing giants who drove stocks to collapse continue extracting maximum profit from concentrated quota ownership worth hundreds of millions. The Radon family’s Givealittle page exposes what 40 years of neoliberal fisheries management has wrought: iwi and small operators left to clean up ecological devastation created by a privatised system that rewards wealth extraction over kaitiakitanga, while David Seymour’s Regulatory Standards Bill threatens to cement corporate control even deeper into Aotearoa’s constitutional framework.

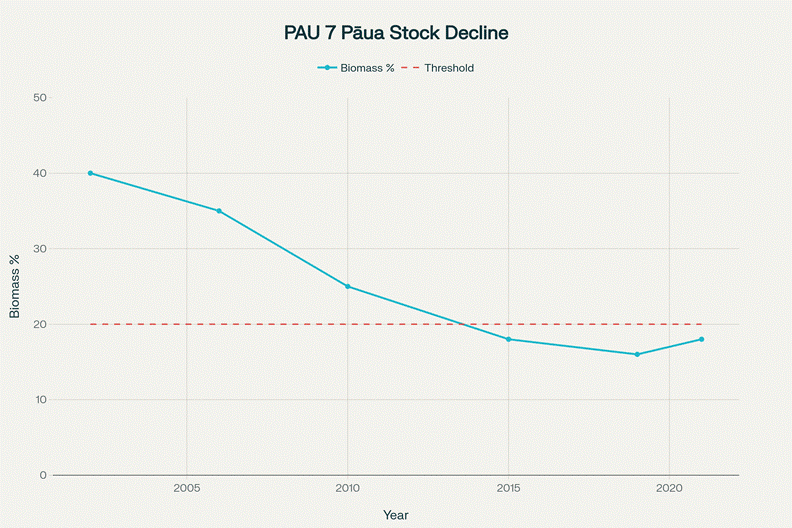

PAU 7 pāua stocks have plummeted to just 16-18% of unfished biomass, well below the 20% threshold requiring mandatory rebuilding, yet commercial fishing continues with concentrated corporate quota ownership.

Whakapapa: How We Privatised the Commons and Called It “Sustainability”

The story of Aotearoa’s pāua begins not in 1986 when the Quota Management System (QMS) was introduced, but in the violent dispossession of Māori from our coastal kaitiakitanga that began in 1840. For centuries before colonisation, hapū managed fisheries through sophisticated systems of rāhui, maramataka, and intergenerational knowledge transmission that maintained abundance (Te Ara Encyclopedia, 2009)(St. Martin, 2006). When Pākehā arrived, they brought with them the doctrine of terra nullius and mare nullius – the genocidal fiction that the land and sea belonged to no one, and therefore could be enclosed and commodified.

By the 1980s, Aotearoa’s inshore fisheries were collapsing under open-access exploitation. The Crown’s response wasn’t to restore Māori management systems or establish genuine kaitiakitanga. Instead, in classic neoliberal fashion, they privatised the commons (Yandle and Dewees, 2008). The QMS, introduced in October 1986, allocated Individual Transferable Quotas (ITQs) based on catch history – effectively rewarding those who had most aggressively depleted fish stocks with permanent property rights to continue extraction (Lock and Leslie, 2007).

The initial quota allocation was a masterclass in state-sanctioned theft. Māori were systematically excluded despite the Treaty guarantee of tino rangatiratanga over fisheries (Connor, 2001). It took Māori injunctions and years of litigation to force the 1989 interim settlement (10% of quota plus $50 million) and the 1992 Sealord Deal (50% of Sealord, 20% of new species quota, $18 million) (Te Ara Encyclopedia, 2009)(Waitangi Fisheries Commission, 2004). Even this “settlement” came with strings attached – Māori quota had to operate within the same extractive capitalist framework that prioritises maximum sustainable yield over genuine sustainability.

The international context matters. New Zealand’s QMS was part of a global wave of fisheries privatisation rooted in the work of neoliberal economists like H. Scott Gordon and Anthony Scott, who argued that “common property” fisheries inevitably led to overfishing – the so-called “tragedy of the commons” (St. Martin, 2006). This narrative conveniently ignored both successful community-managed fisheries worldwide and the fact that Māori had sustainably managed New Zealand’s fisheries for 700 years before Pākehā arrival. Iceland, Australia, and various US fisheries followed similar privatisation paths in the 1980s-90s, creating what critics call “ocean enclosures” (Palsson and Helgason, 1994).

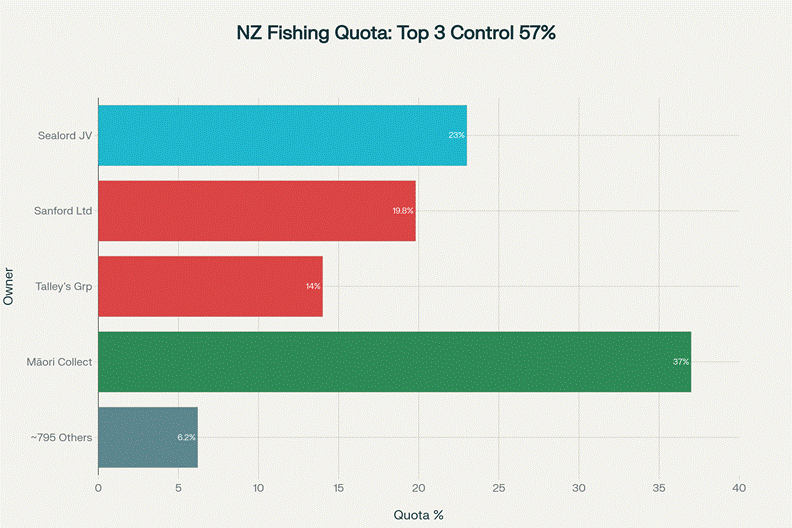

New Zealand’s fishing quota is highly concentrated, with just three corporate entities controlling 57% of commercial quota, while Māori hold 37% through Treaty settlements, and 795 smaller operators share the remaining 6%.

The stakes are massive. New Zealand’s seafood exports are forecast to reach $2.2 billion in 2025, up from $2 billion in 2023, with government targeting $3 billion by 2035 (Jones, 2024)(RNZ, 2025). The fishing and aquaculture industry employs approximately 26,000 people and manages 642 fish stocks across New Zealand’s vast Exclusive Economic Zone (Ministry of Fisheries, 2024)(Seafood NZ, 2020). Yet as quota has consolidated into fewer hands over four decades, the distance between wealth extraction and ecological stewardship has widened into a chasm.

The Issue: A Family Crowdfunding What Corporations Should Fund

On October 31, 2025, The Press published a feel-good story about the Radon family – Mike, Antonia, and their children Sarah, Jacob, and James – who run Arapawa Blue Pearls on Arapaoa Island in the Marlborough Sounds (Brew, 2025). Since 2005, the Radons have hand-raised pāua in 400 specialist tanks, releasing thousands of baby pāua annually to rebuild devastated populations. This year, they partnered with five Hauraki Gulf iwi – Ngāti Paoa, Ngāi Tai, Ngāti Tamaterā, Ngāti Hei, and Ngāti Rēhua – in a “special project” to rescue and grow undersized pāua from Waiheke Island (Brew, 2025).

The article frames this as heartwarming conservation success. But read between the lines, and a darker story emerges. Mike Radon tells The Press: “We’ve had a hard time getting the big commercial companies that own pāua quota to put money in for reseeding” (Brew, 2025). When they started, small pāua diving companies provided support – operators “in the water diving and really had a feel for what was going on.” But over time, quota consolidated into corporate hands: “a lot of that quota has been absorbed by big companies and the corporate-type guys we have to deal with need to show their bosses a profit every year. But we’re looking at things 20, 30, 40 years down the line” (Brew, 2025).

Unable to secure corporate funding, the Radons set up a Givealittle page to crowdfund pāua restoration (Brew, 2025). Let that sink in. A family business and five iwi are asking the public for donations to repair ecological damage caused by a commercial fishing industry worth $2.2 billion annually. Meanwhile, poaching remains rampant. The Radons describe finding a “solid” pāua bed they’d stocked with 160,000 baby pāua ravaged by poachers: “just knocked the population way back again – it just makes you ill” (Brew, 2025).

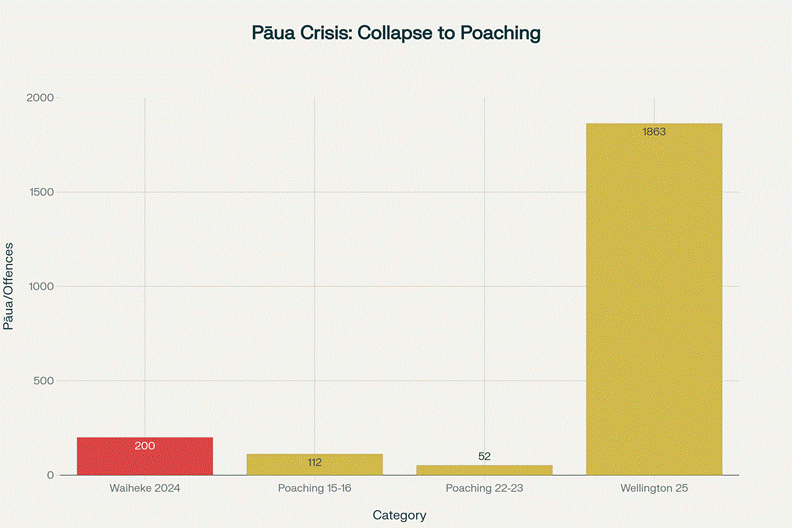

Waiheke Island has only 200 undersized pāua remaining despite a 2021 rāhui, while a single 2025 Wellington poaching bust seized 1,863 pāua worth $25,000, exposing the scale of illegal harvest amid declining national enforcement.

The scale of pāua collapse is staggering. Waiheke Island, where Ngāti Paoa holds mana moana, now has only 200 pāua in traditional beds – all undersized and functionally extinct (Paul-Sumich, 2025)(Skipper, 2024). A 2021 rāhui extending one nautical mile from Waiheke’s entire coastline has had “little result,” according to Ngāti Paoa chairwoman Herearoha Skipper (Paul-Sumich, 2025). The Waiheke Marine Project’s 2024 kōura survey found just 22 crayfish across 2.8 hectares of surveyed reef – down from 23 the previous year (Waiheke Marine Project, 2024). Kōura, like pāua, are “functionally extinct” – unable to perform their ecological role as keystone species (Waiheke Marine Project, 2024).

Nationally, pāua poaching persists despite claims of improved compliance. Fisheries New Zealand reported 112 pāua-related offences in Wellington between July 2015 and June 2016, dropping to 52 in 2022-23 – a decline authorities attribute to Covid-19 impacts and better public education (RNZ, 2024). Yet in June 2025, Wellington fishery officers seized 1,863 shucked pāua from two men at Titahi Bay – one of the biggest hauls in recent times, with an estimated retail value of $25,000 (MPI, 2025). The daily legal limit is five pāua per person. These two individuals had enough for 372 daily bag limits.

The article’s timing exposes further hypocrisy. Just days before The Press published the Radon family story, Fisheries Minister Shane Jones announced the “most significant Fisheries Act reforms in decades” (RNZ, 2025). These reforms, welcomed by Seafood New Zealand and Sealord, will allow “greater catch limits when fish stocks are abundant” and prevent on-board camera footage from being made public under the Official Information Act (RNZ, 2025)(Jones, 2025). When the public can’t see what’s happening on fishing vessels, and quota owners get to increase catches during “abundance,” who wins? Not pāua. Not iwi. Not future generations.

Analysis: Neoliberalism’s Extractive Logic Meets Seymour’s Deregulation Playbook

The Quota Management System: Privatising the Ocean, Socialising the Costs

New Zealand’s QMS is internationally celebrated as “world-leading” sustainable fisheries management (Ministry of Fisheries, 2024)(Owen Symmans, 2020). Industry representatives and government officials repeatedly invoke this narrative. Yet beneath the sustainability rhetoric lies a system designed to maximise extraction while downloading restoration costs onto iwi and small operators.

Here’s how it works. Each year, Fisheries New Zealand sets a Total Allowable Catch (TAC) for each of 642 fish stocks, divided into Quota Management Areas. The TAC includes allowances for recreational, customary, and “other fishing-related deaths,” with the remainder allocated as the Total Allowable Commercial Catch (TACC) (Ministry of Fisheries, 2024). Quota owners receive Annual Catch Entitlement (ACE) proportional to their quota shareholding. They can fish it themselves, lease it to others, or trade it on quota markets.

The problem? Quota ownership has consolidated dramatically since 1986. Research by Dr. Joanna Stewart found that quota concentration increased across important fish stocks from the 1990s through 2011, with the top three quota holders in many fisheries controlling well over 50% of quota (Stewart, 2011). As of 2024, Sealord (50% owned by Māori through Moana New Zealand, 50% by Japanese fishing giant Nissui) holds approximately 23% of national finfish quota (Commerce Commission, 2023). Sanford Limited controls 19.8%, making it “New Zealand’s largest quota holder” by some measures (Sanford, 2023). Talley’s Group holds approximately 14% (Commerce Commission, 2000). Combined, these three entities control roughly 57% of fishing quota. Māori collectively own about 37% through Treaty settlements (Seafood NZ, 2020). The remaining 795 or so quota holders – including small owner-operators like the Radons – share the scraps.

This concentration matters because quota is a tradeable asset, not a public trust. When small operators sold quota to larger companies in the 1990s and 2000s, often under financial pressure, they transferred not just fishing rights but wealth-generating assets (Te Ara Encyclopedia, 2009). By 2000, Sealord’s 50% stake (half owned by Māori, half by Brierley Investments at the time) was estimated at over $200 million (Middlebrook, 2000). In January 2024, Sealord purchased Christchurch-based Independent Fisheries for an undisclosed sum described as “the largest financial transaction in the seafood sector since the Sealord deal in 1992,” adding 46,000 metric tonnes of quota and three deep-water factory vessels (Sealord, 2024). Quota ownership generates revenue through leasing even when owners don’t fish – what economists call “rent-seeking” behaviour (Yandle and Dewees, 2008).

Yet when stocks collapse, quota owners face minimal consequences. Take PAU 7 (the Otago pāua fishery). A 2022 stock assessment found biomass had fallen to just 16-21% of unfished levels (B0) – well below the 20% threshold triggering mandatory rebuilding under Fisheries New Zealand policy (Fisheries Assessment Plenary, 2024). The TACC was slashed by 50% in 2016-17, following a 30% cut in 2002 (Paua Industry Council, 2019). Industry has voluntarily “shelved” (not fished) 10% of quota annually since 2018 (Paua Industry Council, 2019). But shelving is temporary – quota owners retain their asset and can resume fishing once stocks recover. There’s no mechanism to permanently retire quota, nor to compensate iwi and small operators who bear the costs of rebuilding fish stocks through restoration work like the Radons’.

The QMS explicitly separates biological sustainability from economic sustainability, yet scholars argue these are “fundamentally intertwined” (Yandle and Dewees, 2008). The system aims to maintain fish stocks at levels that sustain the wealth-generating capacity of quota holdings – not necessarily at levels that support flourishing ecosystems, abundant customary harvest, or thriving recreational fisheries. Research shows that even when stocks are deemed “sustainable” under QMS metrics, they’re often far below historical abundance (Schiel, 2025). University of Auckland researchers found that legal-sized pāua dominated marine reserves, while fished locations contained mostly undersized individuals – evidence of sustained overfishing pressure (Hanns et al., 2023).

Whose Labour, Whose Profit? The Class Dynamics of “Conservation”

The Radon family story exemplifies what Marxist scholars call “primitive accumulation” in reverse. Instead of corporations extracting resources and leaving communities to clean up, here corporations extract resources, and then communities must pay again to restore what was taken. The Radons operate a complex business on Arapaoa Island: 283 hectares of pastoral farming, a two-tonne pāua quota, 400 pāua hatchery tanks producing 30,000 live pāua annually (10,000 with blue pearls growing), seaweed collection, jewellery production, tourism, and accommodation (Radon, 2023)(Arapawa Blue Pearls, 2024). They employ about 50 permanent island residents, including Fiona Bowler who works full-time extracting pearls (Radon, 2023). Their daughter Sarah makes over US$100,000 (approximately NZ$160,000) fishing salmon in Alaska for two months each year, which she reinvests in the New Zealand operation (Radon, 2023).

This is not a corporate fishing giant. This is a family working multiple jobs across hemispheres to fund conservation that should be industry’s responsibility. Mike Radon has served as an executive of the PAU 3 Industry Association (Arapawa Blue Pearls, 2024). He’s embedded in the industry, understands quota markets, and can’t secure restoration funding from the very companies profiting from pāua extraction.

The five Hauraki Gulf iwi partnering with the Radons face even steeper challenges. Ngāti Paoa’s 2021 Treaty settlement provided $23.5 million total financial redress, including $15.625 million paid in 2013 for the Pouarua Dairy Complex and various cultural redress properties (Ministry of Justice, 2021). For context, that’s roughly equivalent to what one major fishing company might pay for a single vessel and quota package. Yet Ngāti Paoa is expected to restore functionally extinct pāua populations across Waiheke Island’s entire coastline – approximately 93 kilometres of shoreline plus one nautical mile offshore (Waiheke Local Board, 2021).

This is enclosure by another name. Corporations enclosed the ocean through quota privatisation, extracted value for 40 years, and now iwi must pay to restore what was stolen. It’s the same logic that saw Māori dispossessed from land, then required to buy back tiny fragments at market prices through Treaty settlements. The economic violence is structural, not accidental.

From DOGE to Seymour: The Global Deregulation Playbook Reaches Aotearoa

The Regulatory Standards Bill (RSB), introduced by ACT Party leader David Seymour and passed for first reading under urgency on May 23, 2025, represents the next phase of neoliberal consolidation (RNZ, 2025). The Bill establishes “regulatory principles” that all future legislation must consider, including protection of private property rights, limits on taxation and fees, and “equal treatment before the law” (Seymour, 2025). It creates a Regulatory Standards Board, appointed by Seymour as Minister for Regulation, to investigate legislation that fails to comply with these principles (RNZ, 2025).

Critics across academia, law, and civil society have denounced the RSB as a “dangerous” attempt to entrench ACT’s libertarian ideology in New Zealand’s constitutional framework (RNZ, 2025)(Nelson, 2025). Emeritus Professor Jane Kelsey warns it subordinates social considerations, environmental protections, and Te Tiriti o Waitangi to private property rights (Kelsey, 2025). The Waitangi Tribunal held urgent hearings and recommended halting the Bill until proper consultation with Māori occurs (e-tangata, 2025). Former Prime Minister Sir Geoffrey Palmer called it “the strangest piece of New Zealand legislation I have ever seen” (NZ Herald, 2025).

The RSB’s “taking of property” principle is especially insidious for fisheries. It requires that any regulation restricting property use must be justified and potentially compensated (Seymour, 2025). Quota is property. If government moves to reduce catches to protect collapsing fish stocks – as happened with PAU 7 – quota owners could argue their property rights have been “taken” and demand compensation. This flips conservation on its head: instead of polluters paying, the public pays polluters to stop polluting.

The international parallel is unmistakable. In the United States, President Donald Trump’s second term has pursued aggressive deregulation through the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), initially led by billionaire Elon Musk (Reuters, 2025). DOGE’s stated goal was to cut $2 trillion in federal spending by eliminating “waste, fraud and abuse” (ABC, 2025). In practice, DOGE fired 260,000 federal employees (12% of the civilian workforce), cancelled contracts primarily hurting small businesses, gutted agencies like USAID, and gave Musk unprecedented access to sensitive government data (Reuters, 2025)(ABC, 2025). Critics describe DOGE as “state capture” – legalised corruption where private entities shape policy to benefit their interests (Morgenbesser, 2025).

DOGE explicitly emulates Project 2025, the Heritage Foundation’s 900-page blueprint for restructuring the U.S. federal government (Conversation, 2025). Project 2025 advocates dismantling the “administrative state,” replacing civil servants with political loyalists, eliminating environmental regulations, and prioritising corporate rights over public goods (ACLU, 2025)(Democracy Docket, 2024). Russell Vought, Trump’s Office of Management and Budget director and Project 2025 architect, explicitly aims to put career civil servants “in trauma” (Wikipedia, 2024).

Seymour’s RSB follows the same playbook. Like DOGE, it claims to improve “transparency” and “accountability” while actually centralising power in the executive and enabling corporate influence (Seymour, 2025). Like Project 2025, it excludes Te Tiriti from regulatory principles while enshrining property rights (Greenpeace, 2025). And like both, it would make progressive regulation – protecting the environment, workers’ rights, public health – politically and financially costly for future governments.

Seymour himself has acknowledged the connection, comparing his deregulation agenda to international trends. ACT’s coalition agreement with National commits to “cutting red tape” and passing the RSB “as soon as practicable” (Coalition Agreement, 2023). National MPs largely support the Bill despite public criticism, suggesting shared commitment to business-friendly deregulation. This is the fourth time ACT has attempted to pass such legislation; previous attempts in 2007, 2012, and 2021 all failed (Conversation, 2025). The difference now? ACT holds significant leverage in a coalition government, and international momentum for deregulation provides political cover.

Rhetorical Techniques: How Neoliberalism Hides in Plain Sight

The Press article on the Radons employs classic neoliberal framing techniques that obscure structural power. It’s not the journalist’s fault – Andy Brew is simply reporting what he was told. But the effect is ideological.

First, individualisation. The story focuses on the Radon family’s hard work, ingenuity, and passion: “almost like a religion,” Mike says of their pāua conservation (Brew, 2025). This frames ecological restoration as individual choice and personal virtue, not collective responsibility or structural obligation. We’re meant to admire the Radons’ dedication, not question why a billion-dollar industry isn’t funding restoration.

Second, naturalisation. The article mentions that quota “has been absorbed by big companies” almost in passing, as if this were inevitable market evolution rather than deliberate policy enabling consolidation (Brew, 2025). The passive voice hides agency: who designed quota to be tradeable? Who approved mergers? Who benefits from consolidation?

Third, false balance. Poaching is presented as equivalent to commercial overfishing: both are “problems” affecting pāua. But poaching is already illegal and prosecuted. Commercial fishing operates within legal limits set by the same government that under-resources enforcement. These aren’t equivalent – one is criminal deviation, the other is structural extraction.

Fourth, technological solutionism. The article highlights the Radons’ innovative “bucket system” mimicking wave action and their shift to releasing 9-day-old spat instead of 8-month-old juveniles (Brew, 2025). Technology will save us! This obscures that the problem isn’t insufficient innovation but excessive extraction. We don’t need better aquaculture techniques; we need fewer boats, lower catches, and permanent area closures.

Fifth, partnership euphemism. The Radons “partnered” with five Hauraki Gulf iwi (Brew, 2025). Partnership implies equality. But iwi hold mana moana and Treaty-guaranteed kaitiakitanga over these waters. They’re not “partners” in a restoration project – they’re tangata whenua forced to clean up colonisers’ mess.

Shane Jones’ rhetoric around fisheries reform deploys similar techniques. He frames camera footage exemption from the OIA as protecting fisher privacy, not corporate secrecy (RNZ, 2025). He claims reforms promote “sustainability” while explicitly enabling higher catches when stocks are “abundant” – abundance determined by the same industry-funded science criticised for underestimating depletion (RNZ, 2025). He dismisses environmental concerns as “dystopian views” and “fountains of mistruth,” delegitimising critique before engaging with evidence (Jones, 2025).

Hidden Connections: Who Profits, Who Pays, Who Decides

Connection 1: Sanford’s Pivot and the Moana Expansion

In May 2023, Sanford Limited – New Zealand’s largest publicly-listed fishing company with 19.8% of national quota – leased its North Island inshore quota to Moana New Zealand (Commerce Commission, 2023). The deal transferred substantial ACE while Sanford retained underlying quota ownership. Moana, 100% Māori-owned through iwi collective Te Ohu Kaimoana, subsequently acquired 50% of Sealord from Nissui for an undisclosed sum, making Māori 50% owners of New Zealand’s largest fishing company (Sealord, 2024). Sealord then purchased Independent Fisheries, adding 46,000 tonnes of quota (Sealord, 2024).

On the surface, this looks like Māori economic empowerment through Treaty settlement assets. Dig deeper, and it’s quota consolidation accelerating. Moana now controls approximately 1.7% of finfish quota directly, plus leased Sanford quota, plus 50% of Sealord’s 23% (Commerce Commission, 2023). Even accounting for Moana, Sealord, and related entity Westfleet operating independently, aggregated shareholding approaches 30-35% of national quota in Māori-connected entities. This concentration triggers Commerce Commission scrutiny for anti-competitive behaviour, yet the Commission approved Moana’s Sanford lease in 2023 (Commerce Commission, 2023).

Here’s the tension: Māori quota ownership is good, yes? It returns fishing rights to tangata whenua and generates revenue for iwi development. But it operates within the same extractive QMS framework that prioritises maximum sustainable yield over genuine abundance. Moana’s general manager Mark Ngata told RNZ the company installed cameras on its fleet voluntarily to enable “good sustainability decisions” (RNZ, 2025). That’s laudable. Yet when Waiheke’s pāua are functionally extinct, where’s Moana’s restoration funding for Ngāti Paoa? When PAU 7 is at 16% of unfished biomass, why is quota shelving temporary rather than permanent retirement?

The answer is structural. As long as quota is tradeable private property, holders face market pressure to maximise returns. Moana must compete with Sanford, Talley’s, and international buyers. It can’t unilaterally withdraw from fishing without losing quota value. This is what scholars mean by saying capitalism subsumes all alternatives: even Māori ownership gets channelled into extractive logic.

Connection 2: The Radon Family’s Quota and PAU 3 Politics

Mike Radon holds a two-tonne pāua quota in Cook Strait and Kaikōura (PAU 3) (Radon, 2023). He previously served as an executive of the PAU 3 Industry Association, a role his son Jacob now holds (Arapawa Blue Pearls, 2024). PAU 3 covers one of New Zealand’s most valuable pāua fisheries, with quota estimated at $80 million in asset value for the Gisborne region alone as of 2005 (NZ Herald, 2005). The PAU 3 TACC was 121 tonnes as of 2021, with stocks assessed at approximately 40% of unfished biomass – right at the target threshold (Fisheries Assessment Plenary, 2024).

This creates a contradiction. The Radons are small quota owners doing genuine restoration work. But they’re also industry insiders with financial interests in maintaining pāua quota value. When Mike says big companies won’t fund reseeding because they “need to show their bosses a profit every year,” he’s describing his own structural position too (Brew, 2025). His quota is an asset generating revenue through fishing and potentially through lease. If PAU 3 stocks collapsed and TACC was cut by 50% like PAU 7, the Radons’ quota value would plummet.

This doesn’t make them villains. It illustrates how quota privatisation traps even well-intentioned operators. The Radons genuinely care about pāua – their “religion,” Mike says (Brew, 2025). They’re voluntarily releasing thousands of baby pāua annually. But they can’t escape market logic. They need revenue from pearls, salmon fishing in Alaska, farm operations, and tourism to fund restoration. They’re swimming upstream against a system designed to extract, not restore.

Connection 3: Shane Jones, NZ First, and the Iwi Fisheries Paradox

Shane Jones, Minister for Oceans and Fisheries, is a NZ First MP and former Labour Cabinet minister with deep connections to Māori fisheries. He previously worked for the Treaty of Waitangi Fisheries Commission and was involved in allocating fisheries assets to iwi (NZ Herald, 2020). He understands quota markets, iwi aspirations, and commercial realities. His August 2025 fisheries reforms, announced at the Seafood NZ conference in Nelson, are therefore especially concerning (RNZ, 2025).

Jones explicitly frames reforms as supporting industry growth: “catch more fish - if it could be sustainably harvested” and target $3 billion in annual seafood revenue by 2035, up from $2.2 billion currently (RNZ, 2025). He proposes allowing catch limit increases when stocks are “abundant,” more responsive management decisions, and exempting camera footage from the OIA to protect industry “social licence” (RNZ, 2025)(Jones, 2025). He dismisses critics as pushing “dystopian views” and says industry opponents “hope to do damage to this valuable industry” (Jones, 2025).

Yet Jones also says he’ll uphold “rights protected and safeguarded in the Fishery Settlement” and acknowledges customary fishing is “tricky” because iwi have different expectations (RNZ, 2025). When asked about closing depleted fisheries to all sectors including customary harvest, he wavers: “if a fishery is genuinely stressed for a period of time, my preference would be no one has access to that fishery” (RNZ, 2025). But who defines “genuinely stressed”? Industry-funded science that consistently underestimates depletion?

Jones occupies a contradictory position. He’s Māori, understands iwi struggles, and knows fisheries settlement history. But as Minister, he must balance iwi interests, commercial operators, recreational fishers, and environmental groups. His reforms favour industry – Seafood NZ and Sealord both praised them (RNZ, 2025). Labour’s Rachel Boyack, Ngāti Manuhiri Settlement Trust, Greenpeace, and LegaSea all criticised them for prioritising profit over sustainability (RNZ, 2025). The Green Party’s Teanau Tuiono accused Jones of being “bought off by the fishing industry” – a charge Jones dismisses but doesn’t refute with evidence (RNZ, 2025).

Connection 4: The Regulatory Standards Bill’s Fishing Clause That Isn’t

The RSB doesn’t explicitly mention fisheries. Yet its principles would profoundly affect fisheries regulation. Consider the “taking of property” principle: regulations restricting property use must be justified and potentially compensated (Seymour, 2025). Fishing quota is property under the Fisheries Act. Current law allows government to reduce TACC without compensation when stocks decline – quota holders receive reduced ACE but retain proportional quota shareholding. Under the RSB framework, quota owners could argue that catch reductions “take” their property by reducing its value, demanding compensation.

Environmental law scholar Ryan Ward warns this creates a “regulatory takings” regime where corporations can sue for profit loss from public-interest regulation (e-tangata, 2025). International trade agreements include Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) clauses letting corporations sue governments for regulatory changes affecting profits. The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), which New Zealand signed, includes such provisions. Philip Morris sued Australia over plain cigarette packaging under ISDS. Corporations have sued governments for environmental protections, public health measures, and labour laws. The RSB would embed similar logic domestically.

Seymour dismisses such concerns as “alarmism” (RNZ, 2025). Yet the RSB’s Regulatory Standards Board, appointed by Seymour, would investigate “inconsistency” with principles and publish reports pressuring government to comply (Greenpeace, 2025). Over time, this shifts policy towards property rights and away from collective goods. For fisheries, it could make reducing catches politically untenable even when stocks collapse, locking in extraction.

Connection 5: Project 2025, DOGE, and the Global Far-Right Policy Network

The Heritage Foundation, a U.S. conservative think tank, published Project 2025 in April 2023 as a blueprint for restructuring the federal government under a future Republican president (Heritage Foundation, 2023). The 900-page manifesto advocates replacing career civil servants with political loyalists, dismantling agencies like the EPA and Department of Education, eliminating environmental regulations to favour fossil fuels, restricting reproductive and LGBTQ+ rights, and mass deporting undocumented immigrants (ACLU, 2025)(Democracy Docket, 2024).

Trump initially distanced himself from Project 2025 during the 2024 campaign, claiming to “know nothing” about it (Conversation, 2025). Yet his second-term administration has implemented numerous Project 2025 recommendations: restoring Schedule F to enable firing civil servants, appointing Russell Vought (a Project 2025 architect) as OMB director, creating DOGE to slash government spending, withdrawing from climate agreements, and pursuing aggressive deregulation (Conversation, 2025)(Wikipedia, 2024).

DOGE, though not an official department (it can’t be without congressional authorisation), operates as a White House advisory body with sweeping access to federal systems (ABC, 2025). Musk claimed DOGE saved $37.69 billion (later revised to $170 billion) without providing evidence (ABC, 2025)(CNN, 2025). The White House claims DOGE is “extremely transparent,” yet courts blocked its access to Treasury payment systems citing cybersecurity risks and potential improper disclosure of sensitive data (Reuters, 2025). Multiple lawsuits allege DOGE violates civil service protections, union agreements, and constitutional limits on executive authority (Reuters, 2025).

The parallels to Seymour’s RSB are structural, not superficial. Both centralise executive power under the guise of “efficiency.” Both prioritise deregulation and corporate interests over public goods. Both exclude democratic input – DOGE operates outside normal government channels; the RSB passed first reading under urgency with minimal debate. Both create unelected bodies (DOGE, the Regulatory Standards Board) accountable only to a single minister. And both draw on right-wing think tank blueprints developed over decades.

Seymour explicitly embraces these connections. He’s praised Trump’s deregulation agenda and ACT’s policy platform mirrors libertarian frameworks from organisations like the Atlas Network, which links think tanks globally promoting free-market fundamentalism. The New Zealand Initiative, a local think tank funded by corporate members including Fonterra, Fletcher Building, and various banks, has championed the RSB (e-tangata, 2025). This is a coordinated international movement, not isolated policy.

For fisheries, this matters because similar neoliberal frameworks spread globally from the 1980s onward, privatising commons and concentrating ownership. New Zealand’s QMS influenced fisheries management in Iceland, Australia, and U.S. states. Now deregulation proponents cite New Zealand’s QMS as “proof” that market-based systems work, ignoring evidence of stock depletion, quota concentration, and displaced costs onto communities and ecosystems.

Violations of Tikanga: How Neoliberalism Attacks Māori Values

The pāua crisis violates every principle of tikanga Māori.

Whanaungatanga (relationships, connectedness) requires reciprocity and collective responsibility. Neoliberal fisheries management individualises extraction and socialises costs. Quota owners extract value; iwi bear restoration costs. There’s no reciprocity, only asymmetry.

Manaakitanga (care, hospitality, support) demands that those with resources support those without. Corporate fishing giants with hundreds of millions in quota assets refuse to fund restoration work done by a family operation and five under-resourced iwi. Where’s the manaakitanga in that?

Kaitiakitanga (guardianship, stewardship) centres intergenerational responsibility to protect resources for future generations. The QMS defines sustainability as maintaining stocks at 40% of unfished biomass – less than half of what existed before commercial fishing. PAU 7 sits at 16-18% and fishing continues. Kaitiakitanga would demand complete closure until stocks recover to abundance, not “voluntary shelving” that can be reversed when convenient.

Wairuatanga (spirituality) recognises the mauri (life force) of ecosystems. When only 200 undersized pāua remain at Waiheke despite a four-year rāhui, the mauri is broken. Functionally extinct means spiritually dead. Restoring numbers without restoring mauri is coloniser logic – measuring success by quantity, ignoring quality and connection.

Kotahitanga (unity, collective action) calls for working together toward shared goals. Yet fisheries management divides interests: commercial vs recreational vs customary, large operators vs small, Māori quota owners vs iwi without quota. Shane Jones acknowledges this “deeper philosophical debate” but offers no path toward kotahitanga (RNZ, 2025). Instead, reforms strengthen commercial interests.

Rangatiratanga (self-determination, autonomy) was guaranteed under Te Tiriti. Māori would retain tino rangatiratanga over taonga including fisheries. The QMS subordinates rangatiratanga to property rights. Even Māori quota owners must operate within extractive market logic. Ngāti Paoa’s rāhui at Waiheke has legal backing under section 186A temporary closures, yet poaching continues and populations remain collapsed. Where’s the rangatiratanga when iwi lack resources to enforce their own management decisions?

Aroha (love, compassion, empathy) extends to all beings, including non-human relations. Factory fishing treats fish as commodities, not relatives. Maximum sustainable yield calculations quantify fish as tonnage to be harvested, not communities with intrinsic value. When Mike Radon describes finding 160,000 baby pāua they’d raised ravaged by poachers – “it just makes you ill” – that’s aroha (Brew, 2025). The QMS has no space for such grief.

Implications: What’s At Stake and Who Stands to Lose

If current trends continue – quota concentration, deregulatory reforms, RSB passage, and insufficient restoration funding – Aotearoa’s coastal fisheries face ecological and cultural collapse.

Quantified ecological harm: PAU 7 at 16-18% of unfished biomass represents an 82-84% loss of pāua abundance in that QMA (Fisheries Assessment Plenary, 2024). Waiheke Island, with 200 remaining pāua where thousands once thrived, shows over 99% loss. Hauraki Gulf kōura are functionally extinct with just 22 found across 2.8 hectares of surveyed reef – approximately 0.008 per square meter (Waiheke Marine Project, 2024). Snapper stocks in key areas remain depleted despite QMS management. Orange roughy on the Chatham Rise collapsed to 8% of original population in 2025 (RNZ, 2025). These aren’t abstract percentages – they’re species disappearing, ecosystems breaking, intergenerational knowledge becoming obsolete.

Cultural loss: When tamariki can’t gather kaimoana with their kaumātua, cultural transmission breaks. When karakia for fishing become historical curiosities rather than living practice, whakapapa frays. Ngāti Paoa chairwoman Herearoha Skipper captures this: “That’s devastating for us as an iwi but particularly for future generations, to think that my mokopuna will never experience certain kaimoana” (Paul-Sumich, 2025). This is cultural genocide by attrition – not deliberate extermination, but predictable outcome of policies that treat Māori knowledge as irrelevant and Māori customary rights as obstacles to profit.

Economic consolidation: As quota concentrates and the RSB embeds property rights into constitutional framework, small operators face impossible choices: sell to larger companies and exit the industry, or compete in rigged markets where economies of scale favour giants. The 795 small quota holders sharing 6% of national quota can’t meaningfully influence management decisions dominated by Sealord, Sanford, and Talley’s (Commerce Commission, 2023). Even Māori collective ownership, while significant at 37%, operates within the same extractive framework. True alternatives – cooperatives, commons management, abundance-based quotas – become structurally impossible.

Regulatory capture completes: The RSB would formalise what’s already happening informally: industry shaping regulations to serve industry. Shane Jones’ reforms, announced at a Seafood NZ conference with industry representatives present and no environmental groups invited, exemplify this (RNZ, 2025). Camera footage exempt from OIA? Who benefits – the public or corporations? Increased catch limits when stocks are “abundant”? Who determines abundance – independent science or industry-funded assessments? The RSB would entrench this logic: property rights first, public interest second, environmental protection third, Te Tiriti not at all.

International precedent: If the RSB passes and survives judicial review, it provides a template for other right-wing governments. Australia, Canada, the UK – all face similar pushes for deregulation and property-rights prioritisation. New Zealand’s “successful” QMS already influences global fisheries policy. Now our constitutional subordination of collective goods to private property could spread too. This is neoliberalism’s endgame: locking in capitalist extraction so thoroughly that alternatives become legally impossible.

Kua mutu: What Must Be Done

This crisis demands structural transformation, not technical fixes.

Immediate actions:

1. Full quota transparency: Every quota holder, their shareholdings, leasing arrangements, and beneficial owners must be public. No more shell companies hiding concentration. Fisheries New Zealand maintains a quota register but doesn’t publish aggregated ownership analysis. Require annual reports showing quota concentration trends, similar to wealth inequality data.

2. Mandatory restoration levies: All quota holders must contribute to restoration funds proportional to their quota shareholding. If Sealord holds 23% of quota, they fund 23% of restoration. Funds administered by iwi-led governance bodies, not government agencies. Start with 5% of quota value annually – approximately $100-150 million based on estimated total quota value.

3. Permanent area closures: Establish a network of permanently closed areas covering at least 30% of coastal waters, co-managed by iwi with full enforcement funding. Not marine reserves with recreational access – genuinely closed areas where marine communities can rebuild without any extraction.

4. Camera footage public by default: Reverse Jones’ proposed OIA exemption. All on-board fishing camera footage becomes public record after privacy protections for crew (faces blurred, voices anonymised). If industry claims it’s sustainable, prove it. Transparency builds trust; secrecy breeds suspicion.

5. Halt RSB immediately: The Waitangi Tribunal recommended stopping the Bill until proper Treaty consultation occurs. Parliament must comply. If it passes, iwi should injunct under Treaty grounds and seek declarations of inconsistency with the Bill of Rights Act as the Ministry of Justice has warned (RNZ, 2025).

Systemic changes:

1. Quota retirement programme: Establish a Crown fund to purchase quota for permanent retirement, not reallocation. Target collapsed stocks first – PAU 7, Waiheke shellfish, overfished snapper areas. Quota purchased from willing sellers at market rates, then extinguished. Start with $50 million annually, scaling to $200 million.

2. Commons-based alternatives: Pilot community-managed fisheries outside the QMS where local iwi, recreational clubs, and small operators govern collectively. Abundance-based management (fish when abundant, close when depleted) rather than sustained yield extraction. Monitor outcomes rigorously and scale successful models.

3. True cost accounting: Require quota owners to report full environmental and social costs of extraction: habitat damage, bycatch, fuel emissions, displaced customary harvest, impact on predator species. These costs currently externalised must be internalised through adjusted quota allocations and restoration obligations.

4. Redistribute quota to iwi: The 1992 Sealord Deal was a settlement, not reparations. Māori lost 100% control of fisheries and received 37% back. That’s not justice, it’s compromise. A genuine settlement would transfer 60-70% of quota to iwi over 20 years through Crown purchases from willing sellers, enabling Māori-led management systems prioritising abundance over extraction.

5. Constitutional protection for Te Tiriti: Rather than Seymour’s RSB embedding property rights, enshrine Te Tiriti principles in a codified constitution that prevents subordination of indigenous rights to corporate interests. This requires a constitutional convention with guaranteed Māori representation, not government-driven process.

Political mobilisation:

The Māori Green Lantern Fighting Misinformation And Disinformation From The Far Right

Name and shame every MP supporting the RSB. Target National MPs in marginal seats who claim to care about environment or iwi rights yet vote for corporate deregulation. David Seymour represents Epsom, an urban electorate. Run targeted campaigns showing Epsom voters how RSB threatens public health, environmental protection, and democratic accountability – not just Māori interests, everyone’s interests.

Demand Shane Jones resign or be stood down as Fisheries Minister. His conflicts of interest – previous work for the Treaty of Waitangi Fisheries Commission, current role prioritising commercial expansion over sustainability – are untenable. Replace him with someone committed to abundance, not extraction. Ideally, co-governance model with Māori and Pākehā co-ministers.

Support Ngāti Paoa’s and Hauraki Gulf iwi directly. Don’t wait for Givealittle pages. Iwi-led restoration should be Crown-funded as Treaty obligation, not charity crowdfunding. Pressure government to establish dedicated Hauraki Gulf restoration fund of at least $20 million annually, administered by mana whenua.

Build solidarity between environmental groups, recreational fishers, small operators, and iwi. Corporate fishing giants want us divided – “environmentalists want to close everything,” “iwi want special rights,” “recreational fishers are unregulated.” These are lies. We all want abundant fisheries managed sustainably for long-term flourishing. Unite around that common ground.

This is not complicated: Those who extract value must bear restoration costs. Those with power must share governance. Those who profit from the commons must answer to the commons. Everything else is coloniser logic dressed up as “world-leading” management.

The Radon family and five Hauraki Gulf iwi shouldn’t need a Givealittle page. They should have publicly funded restoration programmes as Treaty obligation, environmental necessity, and moral imperative. If we can’t achieve that – if we accept that corporate profits matter more than functioning ecosystems, that private property trumps collective survival – then we’ve already lost.

Kia kaha. Kia maia. The fight continues.

Ko te wai te ora ngā mea katoa

Water is the life-giver of all things

If this mahi has helped deepen your understanding of how neoliberal extraction threatens our moana, and you have the capacity and capability to support this kaupapa, please consider a koha to:

HTDM: 03-1546-0415173-000

He mihi nui ki a koutou katoa.

ACLU (2025). Project 2025, Explained. American Civil Liberties Union. https://www.aclu.org/project-2025-explained

Brew, A. (2025). The Marlborough Sounds family helping baby pāua grow. The Press, October 31, 2025. https://www.thepress.co.nz/nz-news/360856072/marlborough-sounds-family-helping-baby-paua-grow

Commerce Commission (2023). Effects on competition of a fisheries quota lease: Moana New Zealand and Sanford Limited. May 2023. https://www.comcom.govt.nz/__data/assets/pdf_file/0025/317239/Aotearoa-Fisheries-Limited-and-Sanford-Limited-Castalia-report-May-2023.pdf

Conversation, The (2025). How Project 2025 became the blueprint for Donald Trump’s second term. The Conversation, April 25, 2025. https://theconversation.com/how-project-2025-became-the-blueprint-for-donald-trumps-second-term-255149

Fisheries New Zealand (2024). Pāua (PAU 2) – Fisheries Assessment Plenary May 2024 Volume 2. Ministry for Primary Industries. https://fs.fish.govt.nz/Doc/25688/58%20PAU2%202024.pdf.ashx

Greenpeace Aotearoa (2025). The Regulatory Standards Bill is Seymour’s next power grab. July 27, 2025. https://www.greenpeace.org/aotearoa/story/the-regulatory-standards-bill-david-seymour-power-grab/

Jones, S. (2024). Seafood sector a ‘Kiwi success story’. Beehive.govt.nz, December 11, 2024. https://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/seafood-sector-%E2%80%98kiwi-success-story%E2%80%99

Lock, K. and Leslie, S. (2007). New Zealand’s Quota Management System: A History of the First 20 Years. Motu Economic and Public Policy Research Working Paper 07-02. https://motu-www.motu.org.nz/wpapers/07_02.pdf

Ministry for Primary Industries (2025). Fishery officers nab pair with more than 1800 pāua. Media release, June 26, 2025. https://www.mpi.govt.nz/news/media-releases/fishery-officers-nab-pair-with-more-than-1800-paua/

Paul-Sumich, T. (2025). Pāua Power: Can Restoration Efforts Reverse Decades of Decline? Te Ao Māori News, August 4, 2025. https://www.teaonews.co.nz/2025/08/05/paua-power-can-restoration-efforts-reverse-decades-of-decline/

Paua Industry Council (2019). PAU7 Fisheries Plan. https://www.paua.org.nz/_files/ugd/bcdcbd_dfa0b7395c124a9a992145484fc6ef46.pdf

Radon, M. and Radon, A. (2023). Meet the Radon family: Farming pāua and crafting beautiful pearl jewellery in paradise. Our Way of Life, June 6, 2023. https://ourwayoflife.co.nz/meet-the-radon-family-farming-paua-and-crafting-beautiful-pearl-jewellery-in-paradise/

RNZ (2024). Pandemic-era drop in pāua poaching. Radio New Zealand, January 1, 2024. https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/national/505900/pandemic-era-drop-in-paua-poaching

RNZ (2025). Fish farming sector’s biggest opportunity, Oceans and Fisheries Minister says. Radio New Zealand, August 5, 2025. https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/national/569206/fish-farming-sector-s-biggest-opportunity-oceans-and-fisheries-minister-says

RNZ (2025). Major shake-up of fishing quota system on the way. Radio New Zealand, February 11, 2025. https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/business/541638/major-shake-up-of-fishing-quota-system-on-the-way

RNZ (2025). Regulatory Standards Bill passes first reading. Radio New Zealand, May 22, 2025. https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/political/561957/regulatory-standards-bill-passes-first-reading

RNZ (2025). Regulatory Standards Bill slammed as ‘dangerous’ call for ‘alarm bells’. Radio New Zealand, January 12, 2025. https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/political/538784/regulatory-standards-bill-slammed-as-dangerous-call-for-alarm-bells

Sanford (2023). Fisheries Management. https://www.sanford.co.nz/sustainability/fisheries-management/

Schiel, D.R. (2025). Allocations, quota and abalone fishery management. Antipode, 2025. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00288330.2023.2273468

Sealord (2024). Sealord Acquires Independent Fisheries. Media release, January 31, 2024. https://www.sealord.com/2024/02/01/sealord-buys-fisheries/

Seymour, D. (2025). Regulatory Standards Bill promotes transparent principled lawmaking. Beehive.govt.nz, May 6, 2025. https://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/regulatory-standards-bill-promotes-transparent-principled-lawmaking

St. Martin, K. (2006). Neoliberalization and Non-Capitalism in the Fishing Industry of New England. Antipode. https://www.communityeconomies.org/sites/default/files/paper_attachment/St.-Martin-authors-preprint-Diff-Class-Makes-Antipode.pdf

Stewart, J. (2011). Quota concentration in the New Zealand fishery. Marine Policy, 56. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0308597X11000273

Te Ara Encyclopedia (2009). Fishing industry. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. https://teara.govt.nz/en/fishing-industry

Waiheke Marine Project (2024). Latest News: The Kōura were not simply hiding. Waiheke Marine Project. https://www.waihekemarineproject.org/latest-news

Ward, R. (2025). How the Regulatory Standards Bill gives companies more rights than the public. E-Tangata, May 31, 2025. https://e-tangata.co.nz/uncategorised/how-the-regulatory-standards-bill-gives-companies-more-rights-than-the-public/

Yandle, T. and Dewees, C.M. (2008). Sustainability in New Zealand’s quota management system. Marine Policy, Volume 32, Issue 3, 2008. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0308597X16303785

⁂

1. Messenger-Facebook-10-31-2025_12_41_PM.jpg

3. https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/political/562451/what-did-the-house-get-up-to-during-budget-urgency

6. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0308597X16303785

8. https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/rock-lobster-catch-slashed-by-30pc/CP2SXB65FEDBYVTJ7DGVVI6GVY/

9. https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/paua-divers-take-action/BXIHSYJGSULCP27IHYIMHVRTSM/

10. https://www.nzherald.co.nz/topic/fishing-industry/38/

11. https://www.rnz.co.nz/podcasts/rss/voices.rss

13. https://www.reddit.com/r/newzealand/comments/zfli07/puffed_up_fish_gives_family_a_fright_in/

14. https://arapawabluepearls.co.nz/pages/meet-our-team

16. The-Marlborough-Sounds-family-helping-baby-paua-grow-The-Press-10-31-2025_12_40_PM.jpg

18. https://www.paua.org.nz/_files/ugd/bcdcbd_dfa0b7395c124a9a992145484fc6ef46.pdf?index=true

20. https://www.fao.org/4/y2684e/y2684e21.htm

21. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00288330.2023.2273468

22. https://www.newzealand.com.au/tours/paua-pearl-farm-tour/1000

24. https://www.nzlii.org/nz/legis/num_reg/fpqn1984353.pdf

25. https://arapawabluepearls.co.nz/pages/client-testimonials

26. https://motu-www.motu.org.nz/wpapers/03_02.pdf

27. The-Marlborough-Sounds-family-helping-baby-paua-grow-_-The-Press.pdf

28. https://www.nzsportfishing.co.nz/fisheries/species/paua/draft-paua-2-fisheries-plan/

29. https://nz.linkedin.com/company/arapawa-blue-pearls

30. https://www.paua.org.nz/the-qms

31. https://fs.fish.govt.nz/Page.aspx?pk=8&stock=PAU3

32. https://www.rova.nz/podcasts/rex-podcast/episodes/todd-charteris-nzs-150b-farm-succession-conundrum

33. https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/national/505900/pandemic-era-drop-in-paua-poaching

35. https://teara.govt.nz/en/fishing-industry/print

37. https://teara.govt.nz/en/nga-haumi-a-iwi-maori-investment/print

39. https://teara.govt.nz/en/fishing-industry/page-5

41. https://www.nzherald.co.nz/business/nz-fishing-industry-shrinking/LV4HZGXHTO4E7ZS3AH6YVEMQLI/

42. https://teara.govt.nz/en/economy/print

48. https://www.mpi.govt.nz/news/media-releases/fishery-officers-nab-pair-with-more-than-1800-paua/

49. https://www.rnz.co.nz/tags/culture?page=64

51. https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/nze161857.pdf

52. https://www.waihekemarineproject.org/latest-news

53. https://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/poaching-theft

55. https://www.teaonews.co.nz/2025/08/05/paua-power-can-restoration-efforts-reverse-decades-of-decline/

57. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0308597X11000273

58. https://gulfjournal.org.nz/2022/06/decline-of-crayfish-in-marine-reserves/

59. https://www.fishing.net.nz/fishing-news/fishery-officers-smash-major-paua-poaching-ring

60. https://www.rnz.co.nz/search/results?page=73&q=Afternoons+with+Jesse

64. https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/fish-stocks-on-rise-but-theres-a-catch/CGS7CJSQA5SYPYS5I553CZBOAE/

65. https://www.nzherald.co.nz/business/sealord-suitors-biting/6GDT6O6EJKB24GWVDXQO7GLGFM/

66. https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/foresight-needed-to-manage-ocean-treasures/Z2AIPTFESAOS2S56KPPREWQ7OQ/

70. https://media.nzherald.co.nz/webcontent/document/pdf/201324/MIPreport1.pdf

71. https://teara.govt.nz/en/fishing-industry/page-7

72. https://www.nzherald.co.nz/business/talleys-lands-whole-of-amaltal/BIH2YCI4Q6R3R3FAO5CQ3LXZTA/

73. https://media.nzherald.co.nz/webcontent/document/pdf/201351/sixth-national-communication1.pdf

76. https://fs.fish.govt.nz/Doc/25688/58 PAU2 2024.pdf.ashx

77. https://fs.fish.govt.nz/Doc/25692/61 PAU5A 2024.pdf.ashx

78. https://www.sealord.com/2024/02/01/sealord-buys-fisheries/

81. https://teara.govt.nz/en/fishing-industry/page-6

82. https://www.nzherald.co.nz/kahu/cultures-come-together-to-save-fisheries/MH245QFMIFYEIUDZLW3RW5H3WE/

83. https://www.mpi.govt.nz/dmsdocument/49723-Paua-PAU5D-May-Plenary-Report-2021-Volume-2/

85. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0141113625003332

86. https://www.sanford.co.nz/sustainability/fisheries-management/

88. https://www.nzx.com/companies/SAN/analysis

89. https://motu-www.motu.org.nz/wpapers/07_02.pdf

90. https://www.stats.govt.nz/indicators/state-of-fish-stocks/

91. https://teara.govt.nz/en/labour-party/page-4

93. https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/tangled-lines-of-fishing-for-a-feed/IBOEYZXBGDL3CQVL666JSKXL7A/

95. http://media.nzherald.co.nz/webcontent/document/pdf/201116/WEF_GITR_Report_2011.pdf

97. https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/political/566370/anti-red-tape-bill-a-health-risk-doctors-say

98. https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/political/561957/regulatory-standards-bill-passes-first-reading

103. https://www.1news.co.nz/2025/10/13/nz-first-wont-support-gene-tech-bill-barring-major-changes/